The Economic of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB) is about revealing the consequences of our economic choices for nature and (linked to this) for those human livelihoods that depend on nature. It is about addressing the economic invisibility of nature by reorientating our economic compass away from the narrow pursuit of financial gain and towards sustainable development. TEEB recognizes that we cannot manage what we do not measure, and typically we fail to measure the myriad impacts, externalities and dependencies between nature and economic activity. We need to measure what matters to us and reflect this in how we make decisions for our families, communities, economies, and natural resources. In this context TEEB for Coasts is intended to respond to the challenges faced by our coasts.

The birth of TEEB for Coasts

The implementation phase of TEEB has delivered major advances in the fields of natural capital accounting, in how businesses understand their impacts and dependencies on the natural world and especially in advancing the analysis of policy choices around the sustainability of the food systems. So why not do this for our oceans?

The 2012 discussion paper “Why Value the Oceans?” started TEEB’s exploration of applying natural capital concepts to coastal issues. The beginning of the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development in 2021 and the success of the TEEBAgriFood Initiative – actively working with decision makers and researchers in 10 different countries – make this a timely point at which to re-examine what TEEB can offer coastal decision makers, especially understanding the lessons learned from TEEBAgriFood to help contribute to long term sustainable management of our coastal assets.

Making sense of Complex Coastal Systems unsing a Capitals Approach

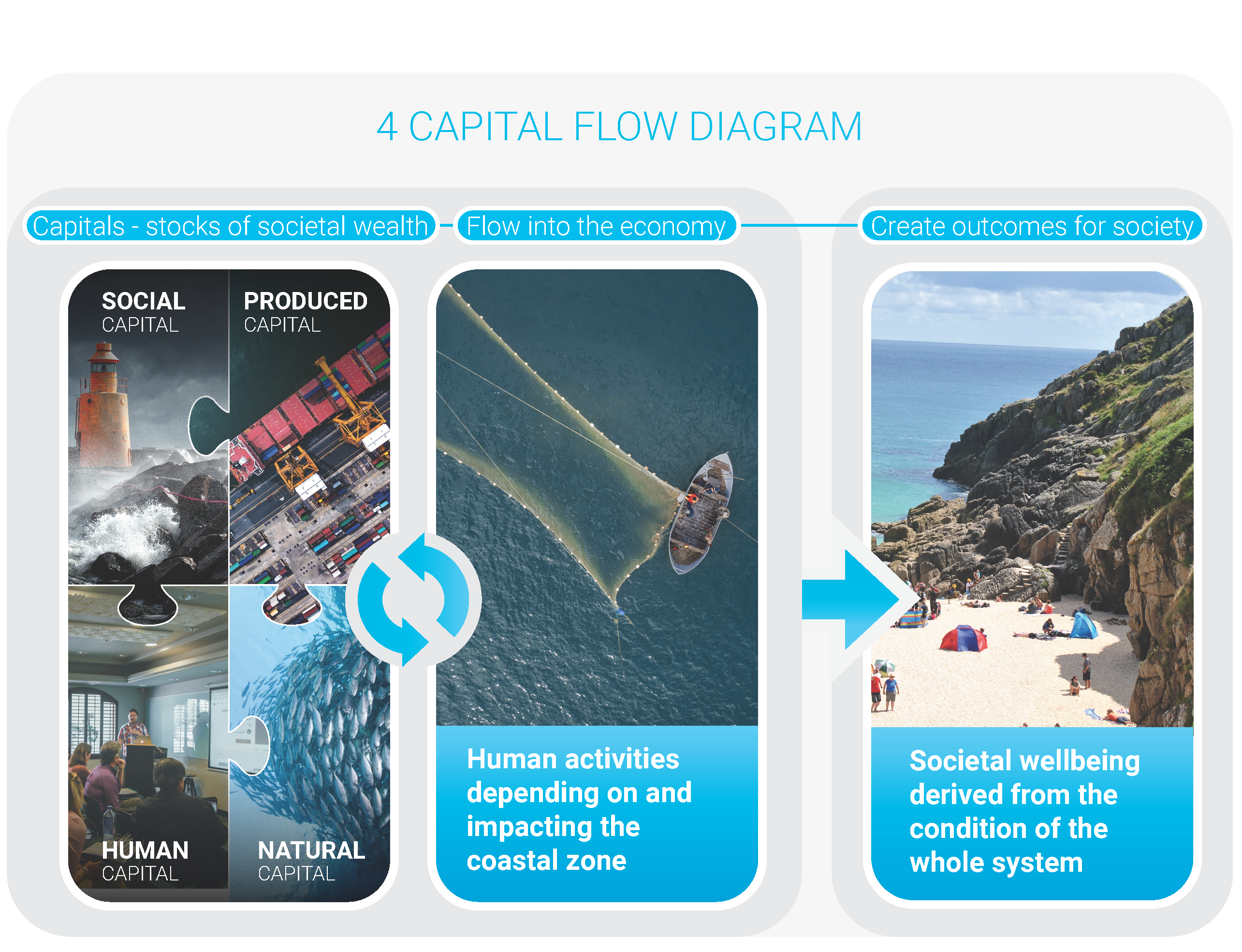

The key to sustainable development is to measure progress in terms of inclusive, societal wealth. For wellbeing to increase, and for that increase to be sustained over generations, it must be based on increasing stocks of capital assets. The size and condition of capital stocks translates to a greater flow of benefits over time. To measure societal wealth and the potential to provide for the wellbeing of current and future generations, we must comprehensively account for ALL capital stocks upon which human wellbeing is built. This means that in addition to accounting for financial and physical capital we must account for natural capital – the natural assets and ecosystems which provide flows of benefits over time. Using a financial indicator such as GDP (Gross Domestic Product) to measure and track development can be misleading because actions that increase GDP may damage and destroy nature, threatening future human wellbeing. We therefore advocate the adoption of a capitals approach. By measuring the four capitals examined in the TEEBAgriFood Framework – Human, Social, Produced and Natural Capital – we can collectively define our ability to meet human wants and needs.

TEEB considers four capitals – natural, human, social and produced. Capitals can be measured in two dimensions, the stock (quantity) and the condition (quality).

Natural capital refers to “the limited stocks of physical and biological resources found on earth, and of the limited capacity of ecosystems to provide ecosystem services” (TEEB 2010). In the coastal area, this stock includes biological resources, such as plankton, fish, and shellfish, coastal land and soil resources, mineral and energy resources, and all ecosystem types (e.g. mangrove forests, saltmarches, seagrass meadows, photic coral reefs, sandy shorelines, mudflats, rocky shorelines, kelp forests, etc.). Natural capital underpins ecosystem services that provide resources and benefits to people. Under the right conditions, natural capital can regenerate. However, if overexploited, natural capital can be degraded and depleted until it no longer provides benefits to society.

Human capital refers to “the knowledge, skills, competencies and attributes embodied in individuals that facilitate the creation of personal, social and economic well-being” (Healy and Côté 2001). In coastal systems, human capital includes the health and skills of fishers, offshore workers, sailors, port operators, dive instructors, hotel staff, etc. that work in the blue economy; it also includes the traditional and indigenous knowledge held by coastal and island communities as well as the production of household services such as raising children. Human capital will increase through improvements in human health, and improvements in skills, knowledge, and education, including traditional and indigenous knowledge. Human capital can depreciate if skills and experience decline, or through deterioration in human health conditions.

Social capital refers to “networks together with shared norms, values and understandings that facilitate cooperation within or among groups” (Healy and Côté 2001). Social capital may be reflected in both formal and informal governance and can be considered more generally the “glue” that binds individuals in communities. Social capital often “enables” the production and allocation of other forms of capital (UNUIHDP and UNEP 2014). Social capital in coastal systems includes policies and laws regulating blue economy sectors, fisheries agencies, coast guards and port authorities, but also community-based governance systems, access rights, community traditions and naval history.

Produced capital incorporates all manufactured capital such as buildings, water and sanitation systems, machines and equipment, physical infrastructure, all financial capital, and the knowledge and intellectual capital embedded in, for example, software, patents, brands, etc. In coastal systems, produced capital ranges from ports, marinas, hotels, coastal roads to boats, ships, offshore platforms, fishing gear, biotechnology patents, applications providing information on tides, oceanographic and meteorological conditions, and blue bonds.

The importance of taking a capitals approach becomes more apparent where two sectors have a shared connection to an asset, as is common in coastal areas. For example, new coastal development such as a hotel or beachside resort, which appeared to be a good investment from a financial perspective, may be a bad choice from a societal perspective. This is because a financial calculation of costs and benefits may fail to account for the wider impacts of the hotel construction. For example, if a mangrove forest needed to be removed in the construction process, the financial cost of carrying this out would be estimated. However, the impacts on the livelihoods of local crab fishers, on the homes of the hotel staff that are no longer protected from storm damage, or the potential negative feedback on visitor numbers if fewer fish are caught by sport anglers as a result of habitat loss would all be missed. Such flows, often ignored by the hotel investor, would be more readily captured in an assessment which shows the uses of and impacts on capital stocks and by engaging all local actors who also use and depend upon those stocks.

By accounting for the Value of Natural Capital we can reduce poverty and develop sustainable livelihoods

Accounting for the value of natural capital in decision making is not a bitter pill that must be swallowed to prevent ecosystem degradation. It is rather an opportunity to reduce poverty and develop sustainable livelihoods. Because many coastal ecosystems have been degraded, restoration of degraded coastal ecosystems could offer significant benefits for many economic sectors. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has estimated that the potential economic gain from reducing fishing harvests to an optimal level and restoring fish stocks is around US$ 50 billion per year. Along with this, mangroves and coral reefs could prevent billions of dollars in flooding damage, offering barriers to storm and wave surges. Currently, mangroves are estimated to prevent $65 billion in damage every year, which is worth significantly more than the timber value of the mangrove trees alone2. Coastal zones also offer new opportunities for renewable, climate friendly energy generation, such as renewable wind, tidal and wave energy, as well as more complex Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion, or marine-based biomass fuels3.

Poorly planned economic growth has demonstrated enormous trade-offs. High concentrations of persistent organic pollutants, heavy metals and plastics in coastal waters – largely from land-based sources – are already associated globally with causing harm to wildlife and humans, including health impacts worldwide through the contamination of fish harvests4. Likewise, the loss of coastal habitats to development will leave over half a billion people more exposed to sea level rise and extreme weather events5. These connections can no longer be neglected and need to be recognized in the choices we make about managing economic activity that impacts our coasts. Given the focus of TEEB on the values of nature in the context of inclusive and sustainable development, a strong focus is placed on revealing the invisible flows connected in particular to natural and social capital.

TEEB for Coasts - An Instrument for Change

TEEB for Coasts provides a logical framework to untangle the complex socio-ecological system of coastal areas, understand the implications of decisions and reorientate the economy towards sustainable development. Completing such a comprehensive assessment will no doubt be challenging. It is easy to excuse inaction due to limited data availability and a lack of political will. However, waiting for the perfect enabling conditions is not an option. Action is needed now. As reflected in a series of expert workshops held as part of the preparation of the Interim Report, even where relationships cannot be quantified, the process, engagement and thinking required to apply the evaluation framework is a great opportunity to break down sectoral and ministerial silos, to reveal hidden trade-offs and rebalance relationships between the economy, people and nature in the coastal zone.

2 Sathirathai, S., 1998. Economic valuation of mangroves and the roles of local communities in the conservation of natural resources: case study of Surat Thani,

South of Thailand. EEPSEA research report series/IDRC. Regional Office for Southeast and East Asia, Economy and Environment Program for Southeast Asia.

3 Arumova, E., Belyaeva, E., Bitarova, M. and Panaseykina, V., 2020, January. Green Economy as a Direction of Sustainable Development of Coastal Areas. In 5th

International Conference on Economics, Management, Law and Education (EMLE 2019) (pp. 192-197). Atlantis Press.

4 IPBES Global Assessment Report - Summary for Policymakers p29 – point 13

5 Global modeling of nature’s contributions to people | Science (sciencemag.org)